News

Poly Connected: Other People’s Stories

Poly launched Poly Connected on February 16. This programming is the newly reimagined Community and Diversity Day. Assistant Head of School, Academics Michal Hershkovitz P’16, ’18 welcomed our guest speaker Professor Camille Rich for Poly Connected: Other People’s Stories for all Middle and Upper School students. This session, the first of four planned events this academic year, will serve as the foundation for our ongoing diversity, equity, and inclusion work to provide all students with a common language in which these discussions will progress, and an imbued empathy from our different lived experiences.

Professor Camille Rich is Associate Provost for Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives at the University of Southern California. She joined the USC Gould School of Law faculty in the fall of 2007 following five years of private practice where she worked primarily on general commercial litigation and internal investigations. Professor Rich has extensive experience working with independent schools, leadership teams, and students of all ages.

Prior to entering private practice, Professor Rich, who is a graduate of Yale Law School, clerked in the Southern District of New York for District Judge Robert L. Carter and on the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals for Circuit Judge Rosemary Barkett.

Poly Connected: Other People’s Stories

Professor Rich presented three sessions during the two-hour community time with students, moving to smaller conversations in Zoom breakout rooms by advisory in Middle School and by grade level in Upper School. Upper School faculty and Middle School advisors acted as facilitators for the discussions.

Professor Rich said she thought it was “a brave thing for your community to do to have these conversations.” She advised attendees these conversations “might be intense.”

Other People’s Stories or American History

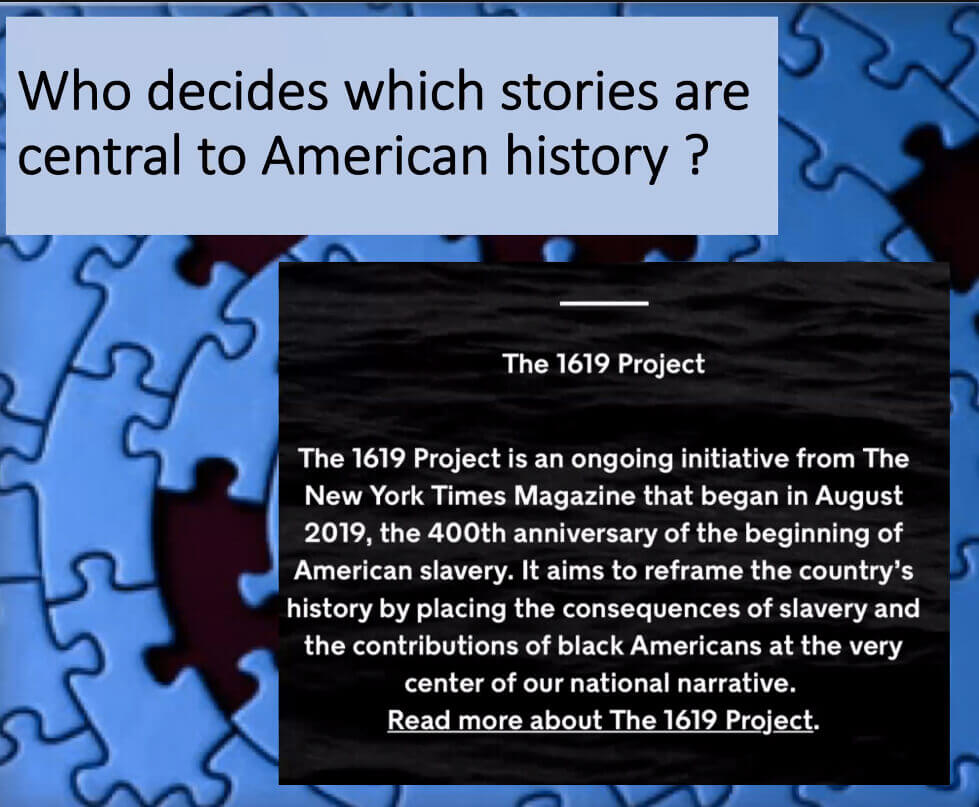

Professor Rich presented the question, “Why has Black history been presented as puzzle pieces?”

She spoke about the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and asked students to consider how the story was discussed in their own families and neighborhoods. “Can you tell the story of the past year without the George Floyd protests story?” she asked. “You are ready now to evaluate the American story you have been gifted thus far. You are ready to identify the missing pieces of the puzzle and ask, ‘What do I gain when I can see the full American story?’”

For the first breakout session, she asked students to consider several questions: Did you discuss George Floyd’s death in class? Did your family have a conversation about the George Floyd story? Were these discussions similar or different? Did you discuss family fears? Family practices? Family identity?

When students returned from the first breakout session, Professor Rich talked again about the George Floyd story, but noted that it was not the only story. She said that there are many other stories such as that of George Floyd that have taken place in America. Many “erasures” of stories characterize our conventional history, she said. She asked students to consider “what stories are important for a full picture to understand American history.”

Professor Rich cited the example of Senator Tom Cotton’s (R-AR) opposition to the 1619 Project, a New York Times Magazine initiative “to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

She went on to tell the story of Seneca Village, a mixed-race community on the site of what is now Central Park. Through eminent domain, the 50 homeowners were forced to sell their homes in 1825 for about $4,000 ($108,000 today) to make way for the building of the park. Professor Rich said Blacks depended on that land for the right to vote; with the sale, they lost the possibility of intergenerational wealth as well as representation at a time when voting depended on property ownership.

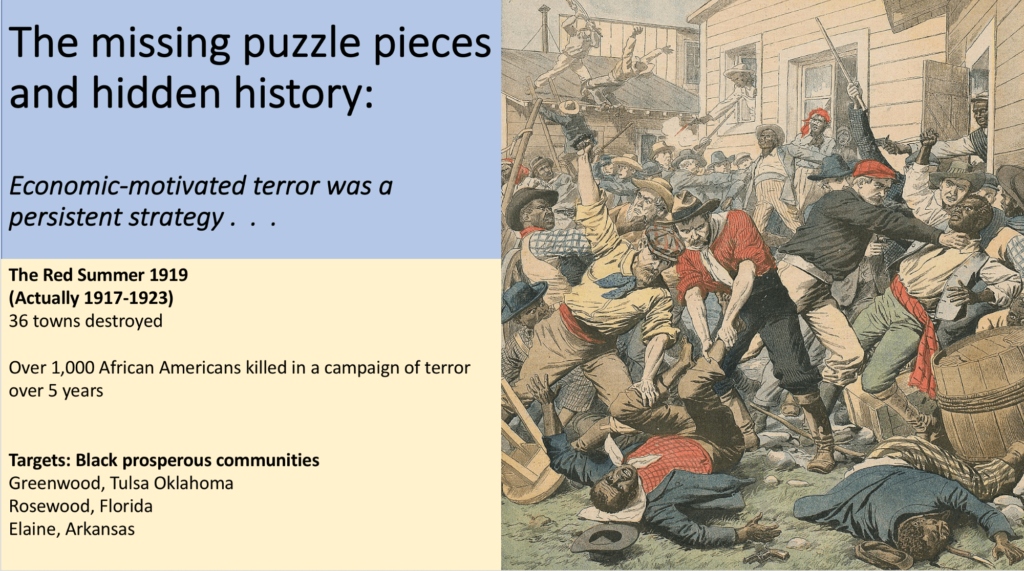

Among the other “missing puzzle pieces and hidden history,” she said, were other events, including “economic-motivated terror,” which was used as a persistent strategy.

During what is called the Red Summer (actually 1917-23), 36 towns were destroyed and over 1,000 African Americans were killed in a campaign of terror. Among the targets were prosperous communities such as Greenwood in Tulsa, OK; Rosewood in Florida; and Elaine, in Arkansas.

In the breakout session, facilitators asked if any students had heard about Seneca Valley. A ninth grader said he had seen a YouTube video. Another student had heard about the Tulsa Massacre from his parents.

“The government has not always been just or right.”

“How does this make you feel?” asked the facilitators. “It changes my perspective,” said one student. “The government has not always been just or right.”

“Why might some people be opposed to claiming or sharing that story?”

“It’s a bloody history,” said one student. “People don’t want to accept it as part of history,” said another. “Part of history is built on lies,” offered another.

Hidden Histories: The Story of Charles Davenport and the Long March of History

Professor Rich suggested that the Red Summer was part of a larger story. “It was about destroying Black wealth,” she said. “What do these stories tell us about the journey to equality?” she asked. “How do these hidden stories complicate the story we tell about the economic struggles of Blacks in America?”

She related these stories to Poly’s own history. Charles Davenport, who was known as the Father of Eugenics, graduated from the Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute, the original Poly Prep, in 1886. Davenport opposed race mixing. Professor Rich shared that Davenport was the author of Heredity in Relation to Genetics, which became “the Bible for the eugenics movement” in the U.S.

Professor Rich then went on to consider the Black@polyprep Instagram page, which includes very painful experiences of Poly students in recent years. She reminded students that they cannot understand a place until they understand its history.

Before having students move to the breakout session, Professor Rich said that “in the Long March of History, your actions … are part of the long march. Future generations will ask, ‘Where were you?’” She asked them to consider, “Why do we hide from other people’s stories?” She added, “The stories are yours even if you are told they are other people’s history.”

“There is so much possibility on the other side of this,” Professor Rich encouraged the students as they moved to the breakout session.

In a breakout session with ninth graders, the facilitator said she had not heard about Davenport and asked students how they felt to hear the story. One student said he thought the story about Davenport was “lost because no one wanted to address it.” But another student said it was “still part of our history.”

Asked to consider Poly’s history, one student said it was “an evolution.”

The facilitator brought up the fact that a recent artist in residence had researched Poly’s history and found that the Dyker Heights campus was founded on land which once belonged to the Lenape tribe, but we do not know when or how they lost their land.

In concluding the sessions, Professor Rich asked students to consider the march of history in regard to Poly’s story. “How do you feel as Poly students?” she asked. “What can we do so we don’t perpetuate [racism]?”

Going Forward

After the program, World Languages teacher Maité Iracheta P’16, shared, “I liked leading a group of students who for the most part I didn’t know. Being a small group as we were, I think the questions we had to explore allowed for a development of individual thought that felt intimate, closed circuit. We were there together in the process of exploring and learning. It was illuminating how some of these ninth graders were connecting dots on the world around them, searching for understanding. My hopes are that the whole student body participates in Poly Connected, weaving the missing pieces of our imperfect human puzzle at Dyker Heights.”

The sessions prompted students and adults to do some research about our own history. “After yesterday’s meeting,” Jack Rudd ’23 said, “I did some research on Charles Davenport. I found some of his family records, and noticed that the surnames ‘Joralemon’ and ‘Pierpont’ ran in his family. This caught my attention because there are streets in Brooklyn Heights named Joralemon and Pierrepont. This makes me wonder… whether or not these street names hold any significance to Charles Davenport or his family. I plan on researching more about how the legacies of oppressors might be immortalized in ways that we often don’t know about and often don’t think twice about. Street names feel very set in stone, and I rarely question their origins. I found this really interesting and I plan on sharing it with my family.”

Bryce Trent ’23 said that the information about Davenport was shocking and upsetting. “From now on I will look more into stories in history,” Trent said, “because there is always something hidden, or over-exaggerated. I was prompted to look more into the Red Summer of 1919 because I only knew about the Tulsa Massacre, and it’s important to learn about all of the massacres that have been hidden.”

“Our first Poly Connected was hard, because working together to identify and interrupt racism is hard,” said Hershkovitz. “It elicited controversy, because we don’t all agree or share the same experiences. But our first Poly Connected also underscored–as we hope all future events in this series also will–that accepting the historical truth and current realities of systemic racism is the only path forward, and that, together, we can build a school and society worthy of our highest ideals.”

Poly Connected continues in March with a visit by artist Dread Scott and a collaboration with Brooklyn High School of the Arts. Professor Rich, meanwhile, will continue her work with members of the administration and student and faculty focus groups until June, as we prepare to welcome Dr. Omari Keeles, our incoming DEI Director, to our campuses.