News

Poly Connected: Social Change through Art

In part one of Poly Connected: Social Change through Art, Poly welcomed visiting artist, Dread Scott, on Tuesday, March 2 during a virtual Middle and Upper School Assembly. Poly students were joined by students from Brooklyn High School of the Arts in an exciting and invigorating new partnership between the two schools. The assembly was followed by a special schedule of workshops on Friday, March 5 to deconstruct the artist’s presentation.

“Inviting Dread Scott marked the beginning of a new school partnership with the Brooklyn High School of the Arts,” said Laura Coppola ’95, P’35, Chair of the Visual Arts Department. “So, conversing and making art with students beyond our immediate Poly community also reflects the kind of work that Dread does, as much of it calls on communities to work and create together for social change. We hope to be able to do that, too!”

Virtual Visit by Artist Dread Scott

Laura Coppola welcomed the students from Brooklyn High School of the Arts and introduced Scott, an interdisciplinary artist.

Scott explained that he is a photographer, painter, and printmaker, and creates street art such as signs and posters. He said, “I make revolutionary art to propel history forward.” Through his art, Scott looks “at the big questions facing humanity.”

Scott, who grew up in Chicago, began as a photographer after receiving a camera from his father. He documented the world of punk bands and considered the writings of Malcolm X and the thinking of Mao on art. Scott became interested in creating art installations with audience participation so as to “extend the dialog in the gallery into the home.”

Scott told the students that in 1988, George H.W. Bush was campaigning for president in flag factories. Scott said, at the time, “large sections of society were not patriotic.” He created an art installation, What Is the Proper Way to Display an American Flag. In this exhibit at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, viewers could stand on the flag, which was on the floor, while they wrote in a comment book. “Artists should trouble the powerful,” Scott said. The U.S. Senate voted 97-0 “to outlaw the flag of the U.S. on the floor or ground” and “the 101st Congress passed the Flag Protection Act of 1989 giving Congress the right to enact statutes criminalizing the burning or desecration of the flag in public protest. This was challenged in United States v. Eichman (1990), and in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the 1989 act on the grounds that the government’s interest in preserving the flag as a symbol did not outweigh an individual’s First Amendment right to desecrate the flag in protest.”

Scott said this experience taught him “the power of art” and made him “want to do more of this.” He subsequently burned the flag on the steps of the U.S. Capitol.

Scott shared another artwork in which he took a banner used by the NAACP to announce a lynching of a Black man and updated it to “A man was lynched by police yesterday.”

Scott shared video (below) of a “community engaged artwork,” Slave Rebellion Reenactment, which documented how he and hundreds of reenactors in period clothing walked 26 miles over the course of two days to reenact an 1811 revolt by enslaved people north of New Orleans. He said the video was about “people who wish to be free from oppressive culture” in an effort to show “how the past sets the stage for the present.”

There was time for questions from the students. “Based on Black Lives Matter, what would you change about your artwork?” asked Mia from Grade 10. Scott said that he had created “banners and signs for recent protests.” He added, “Slave Rebellion Reenactment uses the past to make people think about the present.”

A seventh grader asked why he changed his name from Scott Tyler to Dread Scott. Scott explained the history behind the Dred Scott decision and said he wanted people “to think about that history.”

Afterward, Owen Samra ’24 said, “I love how Dread Scott uses his artwork to provoke and to show new ideas. He uses the audience very effectively, as shown in all of his interactive pieces. He also uses his art to teach people, and to push new boundaries.”

Junie Blaise ‘24 said, “I was excited to see the many intersections within Dread Scott’s work that portrayed historical events and issues that are still relevant today; specifically those highlighting modern day issues and events that are repeatedly glanced over without much in-depth reflection and persuading his audience to have meaningful conversations about these recurring events. Also, I was fascinated in learning more about his revolutionary and performative artworks and the participation aspect of some of his works.”

Middle and Upper School Workshops on March 5

On Friday, Upper School students had a special schedule of about 20 morning workshops, along with about 25-30 students from Brooklyn High School of the Arts. In Middle School, Grades 5 and 6 met for an hour in advisory to view TedTalk – Street Art with a Message of Hope and Peace and created poems inspired by Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (I am an invisible man). Grades 7 and 8 viewed a documentary about artist Keith Haring, and then discussed Dread Scott’s work and also created poems inspired by Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (I am an invisible man).

“Our hope was for the students to take what they heard and saw in the assembly with Dread Scott and expand upon those ideas–how to use art–in all mediums–to bring about change, to open a conversation, to make a point, to share knowledge and experiences.”

Upper School students participated in two workshops, assigned by grade level, at 9 AM and 10 AM. Among the workshops were: Blackout Poetry; Barbed Wire and Haiku: Art and the Japanese Internment; German Coast Uprising through Dread Scott’s work; Political Cartoons and Social Justice; Power, Placement, & Purpose; Reenactments; Sorted Books; Sounds Around Town: A Tribute to New York Lyrics; The Art of Disinformation; The Art of Protest Fashion; The Protest Song: Roots and Relevance Today; Theatre of the Oppressed; Walls for All; and Zines for the Future. “Our hope was for the students to take what they heard and saw in the assembly with Dread Scott and expand upon those ideas–how to use art–in all mediums–to bring about change, to open a conversation, to make a point, to share knowledge and experiences,” said Director of Student Life for Middle and Upper School Alex Davis.

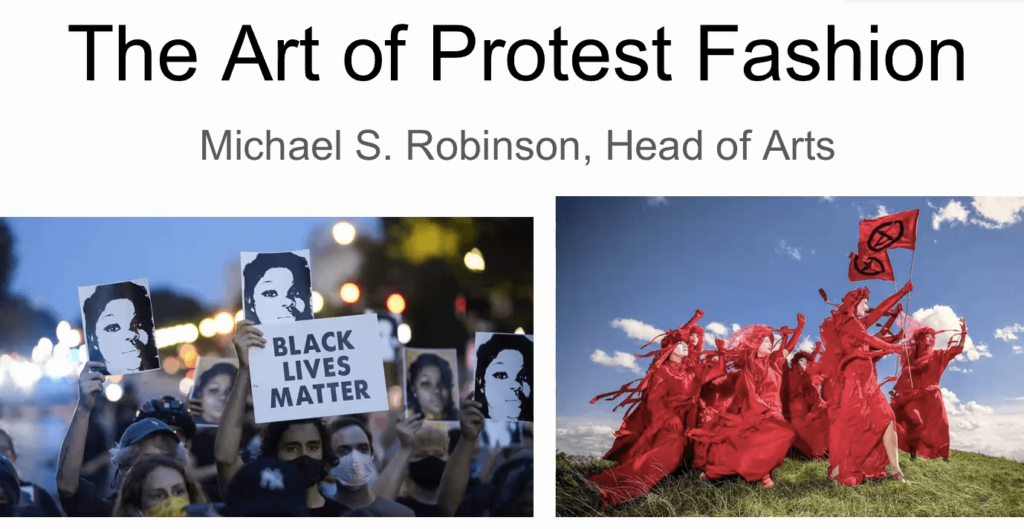

The Art of Protest Fashion

Among the workshops was one presented by Head of Arts Michael Robinson, an internationally exhibited fiber artist, about The Art of Protest Fashion. Robinson welcomed Upper School students who were joined by students from Brooklyn High School of the Arts.

Robinson told students he would give them “a brief overview of the history of protest fashion.” He said his own work in protest fashion has been in the areas of queer identity and anti-gun legislation. Robinson began with suffragettes in the 1800s-1920s who wore white dresses to march in protests. He noted that Black women were also active in these protests. He shared examples of contemporary women, including Vice President Kamala Harris, dressed in white.

Robinson shared a photo of the Silent March of 1917 in which 10,000 marched in silence in an anti-lynching protest. He noted that during the Civil Rights Movement, marchers wore their “Sunday best” in protesting. When Robinson asked for student comments, a BHSA student said he thought they were showing they were “serious about what they were doing.”

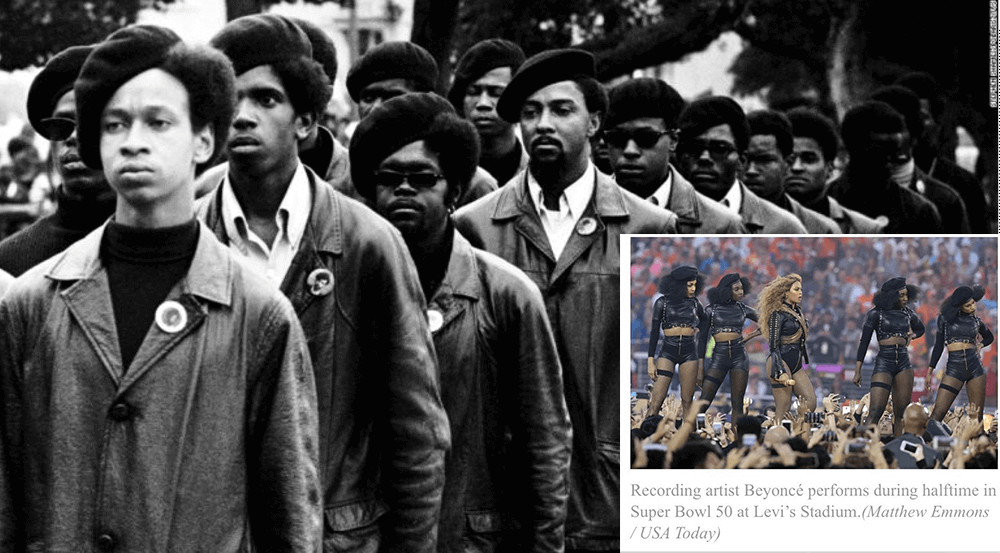

Next, Robinson considered the Black Panthers saying they had a “deliberate style of dress code to be evocative.” This was “a clearly revolutionary style,” which included berets, jackets in the same style like a uniform, and natural hair styles. “This look is translated to Beyonce’s Super Bowl performance,” he said, with the “black berets a nod to” the Black Panthers.

Robinson said the COVID pandemic brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic and friends who died. He talked about ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. In a 1988 photo of artist David Wojnarowicz, Robinson noted a pink triangle on the back of his jacket. He asked the students if they had seen this symbol before. A student identified it as a symbol Nazis used to identify gay people. “This is a powerfully reused symbol,” Robinson explained, “taking a symbol loaded with history and using it in a new way.” In another photo, Robinson pointed out an iconic AIDS era T-shirt: Silence=Death.

On January 21, 2017, five million women marched in the Women’s March, after the inauguration of President Trump, wearing pink hats. Robinson said it was the largest march in Washington, D.C. since the Vietnam War era. “A simple coordinated color made a giant impact,” he said about a photo from the day.

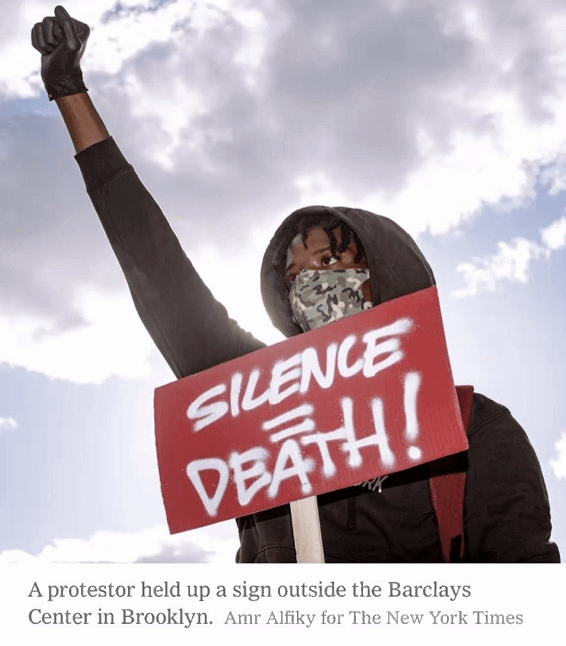

Robinson then considered the Black Lives Matter movement, sharing a 2020 photo of people in BLM T-shirts and raised fists. He added, “We listened to Dread Scott about the use of the flag,” and pointed out a photo of the American flag with the names of police shooting victims written on the stripes. He added that “safety” is a new fashion statement at protests with goggles and masks, some with text on them.

In photos, people protesting violence against Asian-Americans were shown wearing masks with messages such as: “Hate is a Virus.”

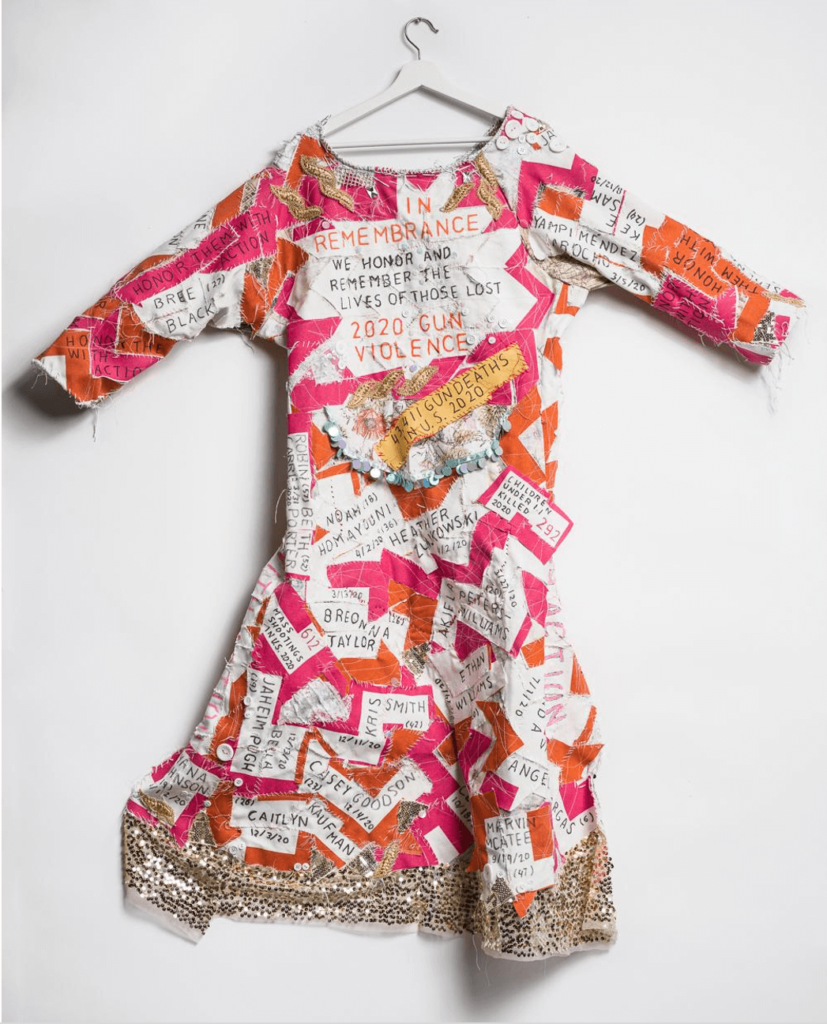

As part of the Gays Against Guns movement, Robinson created a garment, “a wearable art piece,” with a small representation of the names of those killed by guns in the U.S. over 2020, more than 43,000 gun deaths.” It is currently exhibited at the Wisconsin Museum of Quilts and Fiber Arts.

In protests on behalf of missing indigenous people, Robinson said, a red hand print is used. Even more dramatically, photos showed protesters wearing red dresses or red dresses hanging from a laundry line in memory of indigenous women missing in South Dakota. Red is also used by protesters in the global environmental movement Extinction Rebellion, he said.

Workshop: The German Coast Uprising through Dread Scott’s Work

This workshop was facilitated by history teacher Virginia Dillon who said they would look at what Dread Scott had presented as the Slave Rebellion Reenactment in a history context. The German Coast Uprising was an 1811 rebellion by enslaved people in Louisiana, north of New Orleans. She said they would consider “how we understand the past and what is left out.”

“Has anyone ever seen a reenactment?” Dillon asked the students. No one had. She shared that in Charleston, S.C., where she grew up, white people dressed in costumes or uniforms for tours, parades, and Civil War reenactments. Scott’s work made her think about the 1739 Stono Rebellion by enslaved people in S.C. “Dread Scott’s work made it more tangible,” she said.

In the workshop, Dillon and the students considered the flag, a symbol from West Africa, that was used in the Slave Rebellion Reenactment and this led to a larger discussion about “What is the purpose of a flag?” Jake Towey ’23 said that flags are used “to unite or identify a group of people.” In a battle, a flag “tells us where to go, gives identity, gives us direction,” Dillon said.

“What does coming together under one flag mean?” Dillon asked the students. She told them they would do an activity and showed them 12 flags and asked them anonymously to consider about each flag: Would you march under this flag? Would you be willing to march next to someone carrying this flag? Would this flag stop you from joining in a march? She showed them the flags of the United States, New York State, New York City, and the New York Yankees, a Poly banner, the Canadian flag, Rainbow/Pride flag, a “Don’t Tread on Me” Gadsden flag, a peace symbol flag, Blue Lives Matter flag, Communist flag, and a Confederate flag. “Did any of your answers surprise you?” she asked them to consider.

A student said, “Ideals are changing,” and that he didn’t like “swearing allegiance.” Other students said they “would have to know the context behind” each flag.